Service Design Tools Actors Map

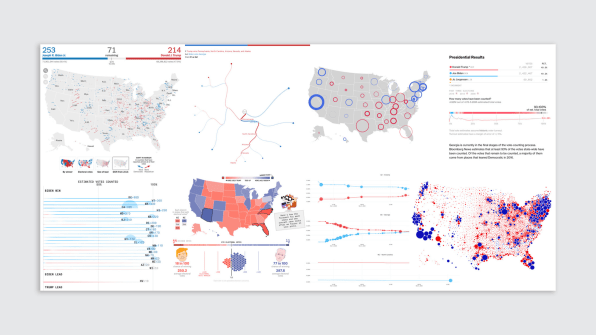

Every election season, maps and charts take center stage on major news outlets and across social media. The public is hungry for numbers and understanding, and data visualizers and cartographers race to produce their best work under tight deadlines, adapting familiar tropes to keep up with unpredictable and fast-moving developments.

As a cartography and data visualization studio, we follow the election map deluge with keen interest. We're constantly sharing election maps and charts in our internal Slack group, discussing which ones are our favorites, and also closely watching which ones seem to get the most attention in the public. As you can imagine, we have opinions. Here are some of our favorite charts and maps from the 2020 election.

Before election night

FiveThirtyEight had our favorite election-night visualizations, as we shared previously. We still think FiveThirtyEight is at the top of its game, especially for data-literate analysis in the lead-up to an election. In 2016, the public at large felt burned by the polling errors and incorrect predictions by most of the pundits, but we'd like to point out that FiveThirtyEight's model (predicting Hillary Clinton with less than a three-in-four chance of winning) was less wrong than the other high-profile models, some of which gave her a 99% chance!

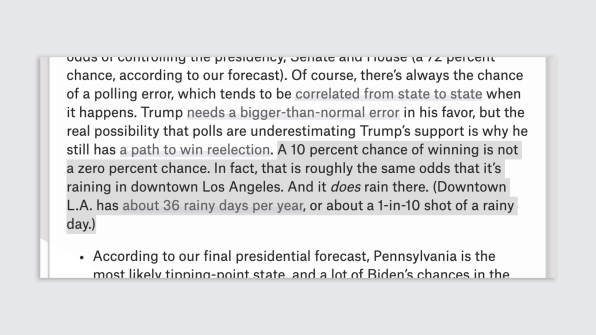

We loved how FiveThirtyEight learned from the public reaction in 2016 and put more effort into its forecast to better explain uncertainty and how probabilities work. For example, FiveThirtyEight's projection for this year (only a 10% chance of a Trump win) was even more confident than in 2016, but they took extra care to explain in plain language that even a 1 in 10 chance is still something that can happen quite often:

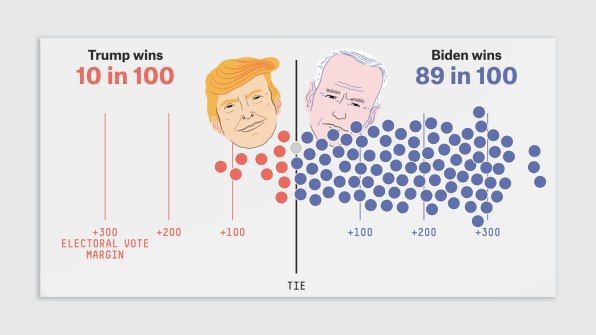

FiveThirtyEight's "beeswarm" chart was perhaps the first iconic visualization of this election season, becoming such a data-viz staple that one data visualizer made it into a Halloween costume.

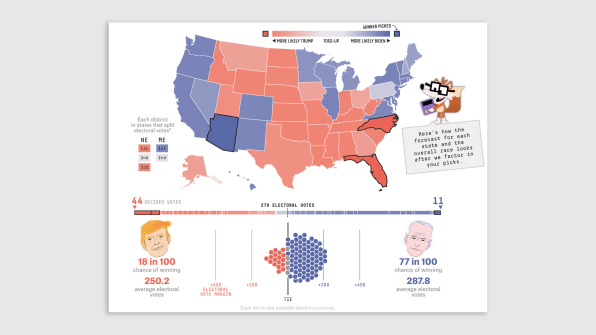

As we approached election night, we liked the interactive model that lets you pick winners in specific states and then see the probabilities for the other states update dynamically:

This tool for playing with different scenarios also reminds us of a classic New York Times "Paths to the White House" visualization from 2012 and this 2020 version from Kerry Rodden, the Electoral College decision tree:

The following day, Shirley Wu live-streamed visualization of voting problems on Election Day.

I wanted to give a visual indicator of the counties that belong to the same states so I tried d3.contours() and finally landed on d3.polygonHull() and ultimately decided to scrap the whole idea bc it just looks confusing but at least I got this animation it's so satisfying ???? pic.twitter.com/W5j0FmnVlE

— Shirley Wu | BLM (@sxywu) November 5, 2020

And for live updates during the election count, we were all curious what would be the loved or hated visualization of 2020 the way The Needle from The New York Times was in 2016. Everyone was traumatized by the stressful shaking needle, but we still need some way to show uncertainty. The Washington Post tried making bar charts (showing the votes that have been counted so far) supplemented by a blurry zone to the right of the bar, showing where the final result is likely to end up, based on the expected demographics of the votes still waiting to be counted. Perhaps this "Fuzzy Bar" would be the famous viz to come out of this year?

Now that Michigan has been called, all (model) eyes turn to Pennsylvania. ????

Donald Trump still leads in counted votes. But currently Joe Biden has a slightly higher median prediction, and a bit more of an upside in potential votes. But A LOT of uncertainty left. pic.twitter.com/Ll1FPKE4Kl

— Lenny Bronner (@lennybronner) November 4, 2020

Oh yes, people loved it:

pic.twitter.com/SWbeG3XSUy

— Bloomberg GFX Teens (@bizweekgraphics) November 4, 2020

Although others found it a bit obtuse:

I have no idea how to read this graph and I read Ulysses

— Q (@QVT) November 4, 2020

Charting the days that followed

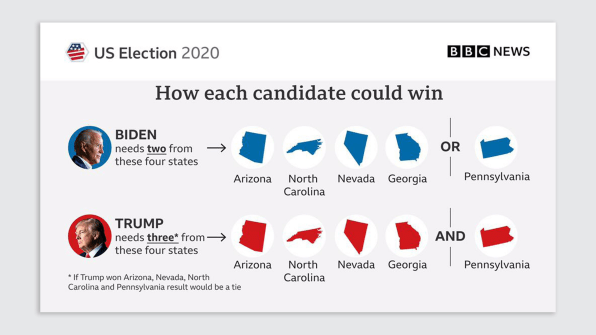

After the first night of election results was over, and most of the state races had been called, we settled in for several more days of vote counting in a few key states. Dynamic "choose your own adventure" maps and scenario modeling tools became much less useful, and the landscape of the remaining Electoral College outcomes could be explained better without a map or a chart at all. Simple infographics like this one from the BBC did an excellent job of telling the reader all they needed to know:

So, for days, all eyes were on these five states, watching as the final votes were counted with agonizing slowness.

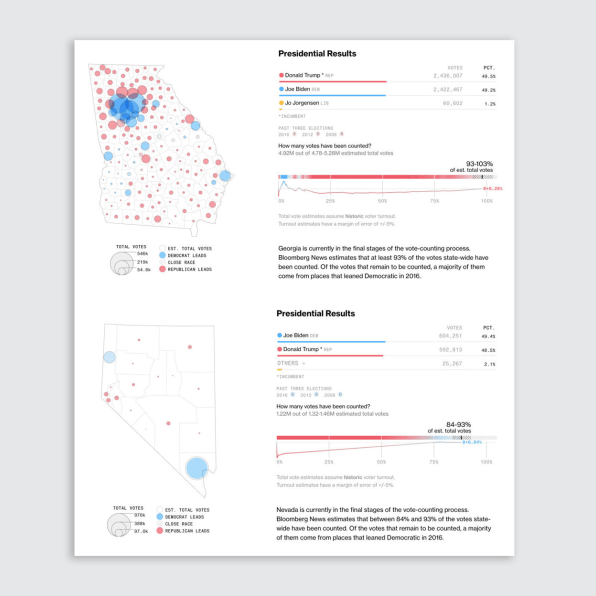

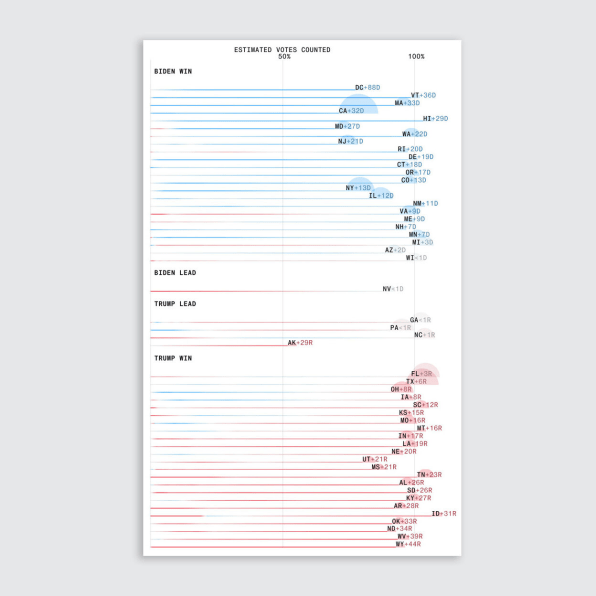

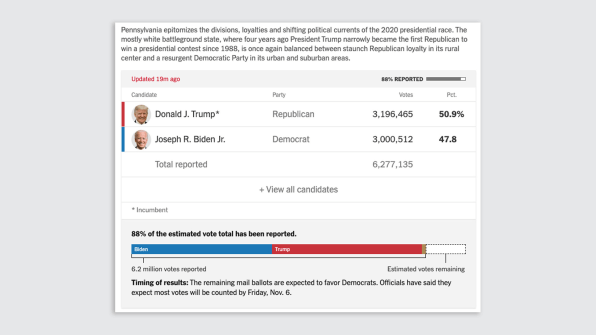

Little did we know (okay, we should have known) that the star visualizations of 2020 would be variations on line charts showing the change in vote margins as votes were tallied. This year there were far more mail-in ballots than ever before, and these would take days to count. Showing partial results was the name of the game, which was quite different from years past.

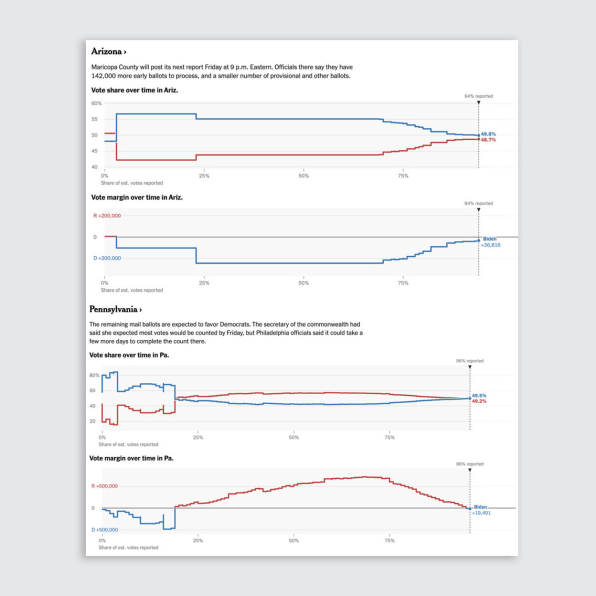

We particularly liked the design of Bloomberg's visualizations, combining a soft color gradient with a line chart to show the shift in the lead as a greater percentage of votes came in:

Here's another Bloomberg variation on those nice soft color gradients, almost as if they were trails left by a group of snails crawling slowly to a finish line.

The New York Times had a similar set of visualizations, which we also liked. The concept was the same: What are the margins over time, and how many estimated votes are likely to come in?

As we watched these charts, we all became amateur election Decision Desks trying to figure out when the patterns were clear enough to be confident in results before all the votes were in. We don't know exactly how the big networks' decision desks do their analysis, but we know roughly that they are carefully studying the trends, and when they are very confident as to where the trend lines will land, they can call the election. As the viewer this year, we got to see those trend lines ourselves, and try to answer the same questions. How many votes might be left? What percentage of the remaining votes does Biden need to overtake Trump?

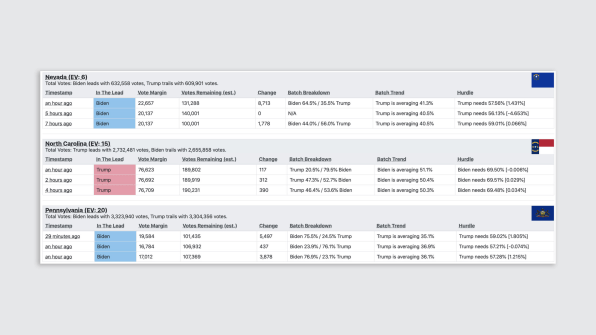

A new trend this year was people using the data feed from The New York Times to develop their own visualizations. This allowed people to develop visualizations that answer the particular questions they have about the data. One popular site based on the Times feed was a live-updating spreadsheet showing precisely the "hurdle" that needed to be met:

And someone else built a visualization of that scraper feed:

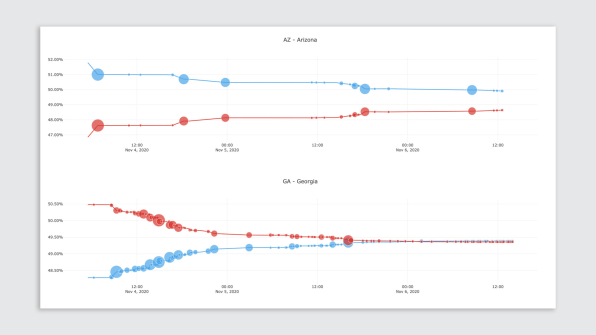

But knowing when the lead would flip would take a scatterplot and a trend line:

BREAKING: Getting ready to cross the X-axis in Georgia.

Gotta love #Trendlines pic.twitter.com/TUaDo1rqGW— John Haurum (@jhaurum) November 6, 2020

Ballots counted over the last ~35 hours in Arizona, Georgia, Nevada and Pennsylvania.

Note that Maricopa County, AZ, has about 200K uncounted ballots outstanding, so Trump's share of those will be key to whether he ends up ahead of Biden. pic.twitter.com/jIR3Gy3Ddx

— Laura Bronner (@laurabronner) November 6, 2020

All of these attempts to chart the trend lines were great, but we didn't see any of them that did a good job illustrating that the trend lines would be different for each batch of ballots depending on their sources (early mail-in ballots versus "late early" ballots mailed just before Election Day) or different geographies (rural areas versus big cities). Watching the live TV analysts describe the vote count, we heard a lot of good verbal explanations about why certain batches of votes were trending specific ways, but so far nobody seems to have put that successfully into a chart.

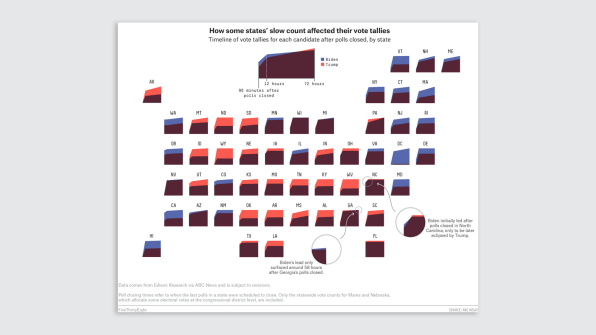

A few days ago, FiveThirtyEight made a nice map-of-charts to explain the "Red Mirage" and "Blue Shift" as it played out differently in each state. We especially like the annotations on this chart:

Mapping the big picture

Laura Bliss at MapLab calls election time "A Mapmakers' Superbowl," and like the Super Bowl, sometimes it felt like watching TV sportscasters:

CNN the last 24 hours pic.twitter.com/a0XJO7de0w

— Michael Kosta (@michaelkosta) November 5, 2020

Who are we to complain when once every four years all of TV becomes the "map show" and when everyone on social media (led by comedian Leslie Jones) has developed a collective crush on Steve Kornacki?

But actual map-based explanations (rather than endless geographical anecdotes from the TV talking heads) felt few and far between. Telling the story about an election is arguably more about the charts and the numbers than the maps. Only occasionally were there clearly mappable geographic patterns (like Cuban-majority census tracts) that had obvious correlation with election results:

pic.twitter.com/GUzpAfzCZF

— Adam Weinstein (@AdamWeinstein) November 5, 2020

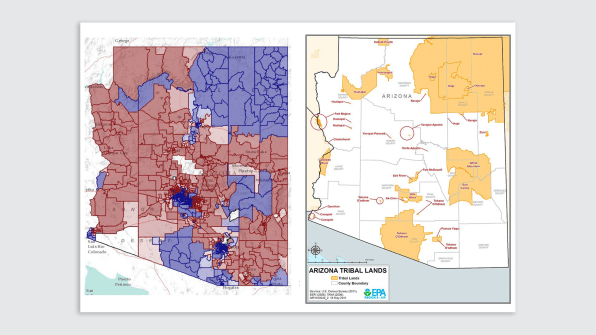

Or this example showing correlation of election results and tribal lands in Arizona:

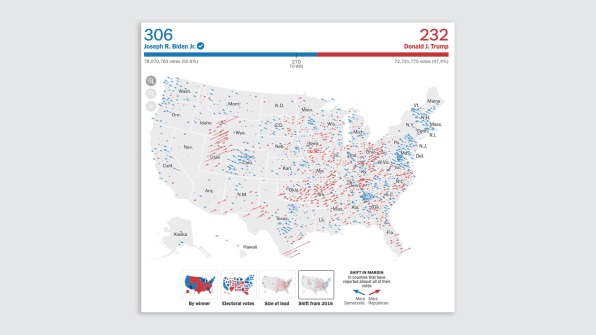

But beyond these few examples, spatial patterns were hard to find. The New York Times's "arrow map" (building on similar maps from 2012 and 2016) showed shifts going in all kinds of different directions with little rhyme or reason. To quote Nate Silver in response to this map: "¯\_(ツ)_/¯"

The Washington Post's had a similar wind map-inspired version, where the upward flow of the lines indicates increased turnout, and the left- or right-ward flow shows a partisan shift from 2016 to 2020. I think we will be unpacking these patterns for quite some time.

Meanwhile, an excellent map meme went around again, showing that you don't need to use the current election's data to tell a story that is still relevant today:

Now "classic" viral maps are re-emerging for a 2nd round – this gif made by @karim_douieb was created in the wake of Lara Trump posting the infamous "Impeach This" county choropleth map. I've seen this in a few cases where a few viral maps see waves of engagement over months/yrs. https://t.co/wDzGmepkvY

— Anthony Robinson (@A_C_Robinson) November 5, 2020

Similarly, as attentions turned to the imbalances of the Senate, this map (annotated by Steve Chiotakis of KCRW-FM radio in Santa Monica, California) went viral across our feeds:

I added some numbers: https://t.co/SNJCujCtwY pic.twitter.com/iLTcc1UhRJ

— Steve Chiotakis (@RadioChio) November 6, 2020

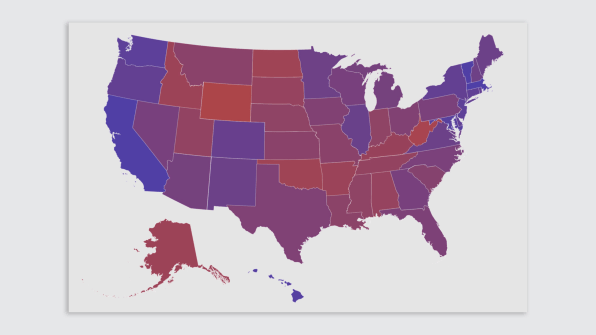

And every year there is an outcry about the inaccuracy of the ubiquitous election maps showing each state either in solid red or solid blue. Again so it was this year, with a "Purple States of America" map by Greg Albers going viral:

Whether or not the purple maps are more "accurate" (we might argue that the harsh solid red and blue maps do a better job telling an accurate story of the Electoral College's inherent first-past-the-post flaws), the Purple States of America site links to some interesting research showing that purple maps make viewers perceive the country as less polarized. By showing showing the polarization of Electoral College votes in stark red and blue, are cartographers creating more polarization in the minds of map readers?

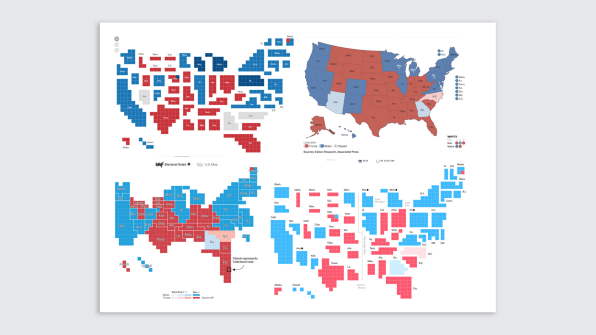

Cartograms were also popular this year (as always), although a slightly less confusing variation from Le Monde (using disconnected cartograms floating on recognizable state shapes) got a lot of likes among the non-cartographers in our network:

I prefer the US electoral map presented this way in the French newspaper, Le Monde.https://t.co/hz986c7WIw pic.twitter.com/gOgQgd4Kvz

— CyberSec Chey (@chey_cobb) November 6, 2020

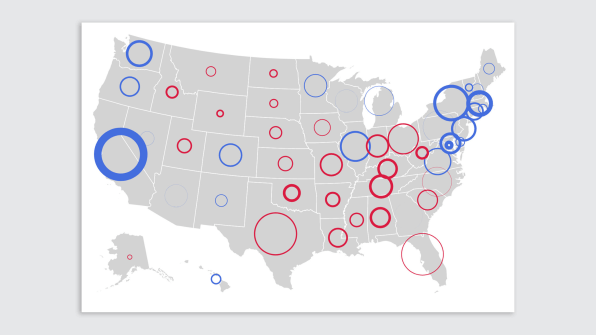

As another way to rethink the endless red-blue maps that tell us little about population or the closeness of the race, the print edition of The New York Times had a map showing county vote margins as proportional circles. These margins are correlated with population, but not always: In some cases, high-population areas almost disappear on this map. A metro area with narrow margins (like Phoenix or Las Vegas) shows up as a tiny dot, and counties such as Tarrant County, Texas (home of Fort Worth and a population of 2 million people) doesn't even show up because Biden and Trump split its votes almost equally.

In the print edition of today's NYTimes, a full-page map of the presidential results so far showing the margin of victory for each candidate, county by county. pic.twitter.com/ZVR7VlIvUm

— NYT Graphics (@nytgraphics) November 6, 2020

If we read the comments on that tweet, we see that most people viewing this map don't understand that it's mapping margins of victory; almost all of them think it's a representation of population.

If we want to map only the margin of victory, what if we map these as rings instead of dots? We put together a quick prototype using VizHub to see if this method would work. In this map, the outer radius is the number of votes for the winning candidate in each state, and the inner radius shows the number of votes for the loser:

Effectively this map only shows excess votes, basically the wasted "extra" votes that are just running up the score. The inner radius shows the votes for the losing party in each state, and the outer radius shows the winning party. So a high-population state with a narrow win would be a big thin circle (like Florida or Texas) and a big state with a wide margin is a big thick circle like California.

This map shows a major flaw in our our Electoral College system of electing the president. Once you have enough votes in a state to win a plurality there, any extra votes are wasted. These extra margins don't do anything to offset your opponent's votes in other states. All of those thick red circles in states like Oklahoma and West Virginia represent votes that could have helped Trump win if they were in other states. The big blue circles in California and New York represent millions of surplus Biden votes that didn't gain him any extra electoral votes. It's no surprise that in most states the outcome is already determined, so that voters don't feel like it makes any difference whether they vote or not (for president at least).

In conclusion

This year we saw continued refinement of traditional election maps styles, and an exciting (and nerve-wracking) new frontier developed with the visualization of post-election ballot counting. Data-viz practitioners are struggling with challenges of how to show uncertainty and how much uncertainty can be shown while still making our visualizations clean and easy to understand. Election cartographers are dealing with their own dilemma of how much to show the polarization and inequality that currently exists in our electoral system (with the risk of reinforcing it) versus making counterfactual maps of systems that could or should be.

Alan McConchie is the lead cartographer at Stamen Design, a mapping and data visualization studio based in San Francisco. He lives in Bellingham, Washington, where he is the cofounder of the nonpartisan election reform group FairVote Washington. Follow him on Twitter, and follow Stamen on Instagram.

This essay was adapted with permission. Read the original here.

Service Design Tools Actors Map

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/90575894/we-design-maps-for-a-living-heres-who-got-the-2020-election-right

Posted by: randolphimesers.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Service Design Tools Actors Map"

Post a Comment